The Car and the Bridge and the Human

She crashed her car into the bridge. She watched. She let it burn.

She crashed her car into the bridge. She watched. She let it burn.

She crashed her car into the bridge. She watched. She let it burn.

She…

Here is what actually happened on that summer they when he was gone. Either Caroline or Aino, nobody knows exactly, let her car crash into the bridge and she watched and she let it burn. And she also threw his shit into a bag and pushed it down the stairs. And she didn’t care. And she loved it.

That summer day most likely happened in 2011. As far as I remember the event was unknown in Austria until end of 2013 or even begin of 2014, I can’t really recall. But once the story of that summer day became known, it was suddenly everywhere.

The song’s omnipresence was utterly annoying. I literally couldn’t stand it.

I crashed my car into the bridge. I watched. I let it burn.

In each and every coffee shop in Austria.

I crashed my car into the bridge.

On each and every local radio station in Slovenia.

I watched.

In each and every coffee shop in Croatia.

I let it burn.

But then, unexpectedly, I started loving the song.

I crashed my car into the bridge.

And I started singing it.

I watched.

And I still sing it here and there.

I let it burn.

Many months passed until recently another one omnipresent tune, slightly different in tone, stuck into my ear. It’s Rag’n’Bone Man’s Human. I’m sure you have heard it:

I’m only human after all, I’m only human after all.

The first catchy tune has never produced any software development related connotations in my head (although I recall seniors talking about software crashes that actually did cause test engines explode and burn, but that’s a whole other story). But the second catchy tune did produce an association and it still does.

I’m only human after all. I’m only human after all. And human do mistakes. And so do I. And although we do them, it must not happen that our human mistakes hurt our customer’s precious data.

Sometimes when I loudly sing Rag’n’Bone Man’s Human three words run through my head. Human. Fault. Tolerance.

Before digging deeper into the meaning of those three words, I have a memorable story to share. It is, of course, deeply connected to human-fault tolerance.

UPDATE DESTROY Table WHERE Condition

There were three of us in that call. Me working from home and two younger colleagues sitting in the office and kindly asking for assistance. There was apparently a slight manual data update that was needed to be done on the production database. They didn’t feel comfortable running update scripts over live data on their own. And so they called me, the Chief Master Hero ™ of our small software company at the time.

Is there any better opportunity to demonstrate fearlessness and confidence in front of your colleagues then running update scripts on a production database in the middle of a working day? Running them, of course, right out of the SQL Server Management Studio with auto-commit set to On. If something goes wrong, there is no way back. But hey, what could possible go wrong? Am I not the Chief Master Hero ™ of our small software shop? And besides, rollbacks are for cowards.

I quickly wrote and run the first simple update script. The colleagues were looking at my shared desktop. And I knew what I was doing was a bad idea. That baaaad feeling in my gut. Very bad feeling. “This is not engineering”, a voice in my had was telling me. “This is a high-wire walk between the Twin Towers on a windy day.”

“I am maybe the Chief Master Hero ™ of our small company, but Philippe Petit I’m surely not.”

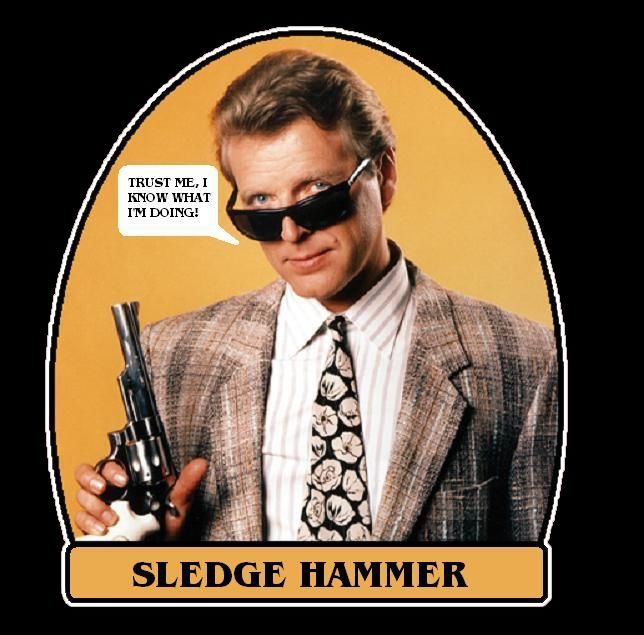

Still, I continued walking the high-wire. The update went well. I pretended ultimate calmness. “Hey, I do this every day.” The second simple update script was also done, typed in a less then a minute. And then again that voice: “This is a baaaad thing you are doing right now, Igor!” The colleagues were quiet. But I knew they were thinking the very same. “This will not end up well.” Still they didn’t dare to verbally oppose my overconfidence. I hid my doubts behind jokes and quoting Sledge Hammer.

Trust me, I know what I’m doing.

The second update went well.

The third update script was equally simple. I typed it down quickly, gave it a short look and pressed F5 with the same speed Sledge was pressing the trigger of his .44 Magnum.

And while the bullet was flying right into the heart of our database, down to the, arguably, the most important table in our system, my brain started to process the WHERE clause of the update just fired.

Hmmmm, it asked, those

A and B or C

aren’t they supposed to be

A and (B or C)

It turned out that, yes, B or C were supposed to be in parenthesis. Logical operator precedence together with the fact that at the very moment I pressed F5 roughly 90% of the rows in our Most Precious Table evaluated true for C literally destroyed our customer’s data.

Just the number of updated rows reported back by the SQL Server Management Studio, way too high number of updated rows, immediately told us that something went really bad. We were quiet for a while. And then the phones started ringing. “Don’t worry”, I said, “I’ll fix it right away. Just calm the customers down. Everything will be fine.” I tried to sound confident. I’m not sure how convincing I was.

I hang up the call and started sweating. “Backup! Where is the backup? Where is the backup?” I wasn’t the one setting up the backup procedure but I knew that backup script was running twice a day. “We will explain it to customers somehow. It’s just few hours of their work. Not a big deal. They will understand. Everything will be fine. Backup? Where is the backup?”

Remotely connected to the database machine I went directly to the predictable C:\Backup folder. The OurDatabase.bak file was there indeed. That single, quite large bak file, created to save us from machine failure, was suddenly supposed to serve a purpose we never thought of before. Saving us, namely, from human failure.

And then, while clicking on the backup file, with a corner of my eye I saw something that literally made my jaw drop. Right next to the file name, there was a fact that my brain actively refused to believe in. “No! No! No! This cannot be! This is a joke! This cannot be real! This is not happening!” The backup was scheduled around lunch time, when the database traffic was low. My colleagues called me just before the lunch time. The backup was triggered literally couple of seconds after my update script destroyed the data and it finished by the time I connected to the database machine. That single bak file I was looking at, a file not older then a minute, contained perfectly safe and at the same time perfectly corrupted version of our Most Precious Table.

To shorten the story, it turned out that the colleague who was creating the backup infrastructure did his job better then I was doing mine. The C:\Backup was just a pick-up folder (of course; after all, what is the point of keeping the database backup on the same hard drive where the database is?). The backup files were uploaded to other network locations, where several previous versions were kept in safety.

Our customers lost six hours of their work that day. No one tried to put the blame on me. But even if somebody did try, what would it change?

I’m only human after all, I’m only human after all. Don’t put your blame on me.

Rather make sure your architecture is human-fault tolerant ;-) Which is exactly the topic of the following chapter :-)

Nathan Marz on Human-fault Tolerance

Those long minutes between pressing F5 and getting back the six-hour-old but still consistent data thought me forever the importance of the human-fault tolerance (beside the obvious lesson in serious lack of professionalism!).

I’m only human after all. Same as my colleagues and millions of other developers worldwide. We do mistakes. We deploy bugs into production. Sometimes we do obviously stupid things.

Data systems should must be designed to be human-fault tolerant.

So far I haven’t stumbled upon any better explanation of the necessity of human-fault tolerance in data systems, then the one written by Nathan Marz in his excellent book “Big Data - Principles and best practices of scalable real-time data systems”. Over and over again, through the whole book, Nathan emphasizes and explains why “it’s imperative for systems to be human-fault tolerant”.

I doubt I could explain or emphasize it better then he did, or even only rephrase it good enough. So, the rest of the chapter consists solely of quotes from his book.

Mistakes in software are inevitable, and if you’re not engineering for it, you might as well be writing scripts that randomly corrupt data (Does any of this ring a bell Igor?). Backups are not enough; the system must be carefully thought out to limit the damage a human mistake can cause.

Human error with dynamic data systems is an intrinsic risk and inevitable eventuality.

The lifetime of a data system is extremely long, and bugs can and will be deployed to production during that time period.

Because data systems are dynamic, changing systems built by humans and with new features and analyses deployed all the time, humans are an integral part of any data system. And like machines, humans can and will fail. Humans will deploy bugs to production and make all manner of mistakes. So it’s critical for data systems to be human-fault tolerant as well.

People will make mistakes, and you must limit the impact of such mistakes and have mechanisms for recovering from them.

And if there’s one guarantee in software, it’s that bugs inevitably make it to production, no matter how hard you try to prevent it.

If the application can write to the database, a bug can write to the database as well.

It bears repeating: human mistakes are inevitable.

The inevitability of human mistakes brings us to the first of The First Principles of Data Systems described in the chapter 1.5 of Nathan’s book - “Robustness and fault tolerance”.

It’s imperative for systems to be human-fault tolerant.

Human-fault tolerance is not optional.

Human-fault tolerance is a non-negotiable requirement for a robust system.

I knew our new architecture not only had to be scalable, tolerant to machine failure, and easy to reason about - but tolerant of human mistakes as well.

The importance of having a simple and strongly human-fault tolerant master dataset can’t be overstated.

Nathan sees the classical, mutable, fully-incremental data systems as inherently non-human-fault tolerant.

And because the databases are mutable, they’re not human-fault tolerant.

With a mutable data model, a mistake can cause data to be lost, because values are actually overridden in the database.

The last problem with fully incremental architectures we wish to point out is their inherent lack of human-fault tolerance. An incremental system is constantly modifying the state it keeps in the database, which means a mistake can also modify the state in the database. Because mistakes are inevitable, the database in a fully incremental architecture is guaranteed to be corrupted.

You saw how mutability - and associated concepts like CRUD - are fundamentally not human-fault tolerant. If a human can mutate data, then a mistake can mutate data. So allowing updates and deletes on your core data will inevitably lead to corruption.

The solution Nathan proposes and promotes in his Lambda Architecture is immutability of the core data and recomputation-based algorithms over those data.

If you build immutability and recomputation into the core of a Big Data system, the system will be innately resilient to human error by providing a clear and simple mechanism for recovery.

Human-fault tolerance - this is the most important advantage of the immutable model. […] With an immutable data model, no data can be lost. If bad data is written, earlier (good) data units still exist. Fixing the data system is just a matter of deleting the bad data units and recomputing the views built from the master dataset.

In this regard, recomputation algorithms are inherently human-fault tolerant, whereas with an incremental algorithm, human mistakes can cause serious problems.

The only solution is to make your core data immutable, with the only write operation allowed being appending new data to your ever-growing set of data.

If any of this sounds exaggerated and unconvincing at first sight, I strongly recommend to you to read the Nathan’s book “Big Data - Principles and best practices of scalable real-time data systems”. And other way around, even if his reasoning sounds logical and clear, the book is anyway a great read.

Brothers In Arms

“Human”, said Dr. Louise in Arrival. “I’m human. I’m hu…”

I was wandering how comes that aliens didn’t learn at least a bit of English on their own before meeting Dr. Luis. It shouldn’t be that hard for a superior race of their kind. But let’s trust the movie and accept the fact that Dr. Luis herself taught them that she is a human. I assume they quickly figured out that the rest of us are humans as well.

Did any of those humans, of us - I asked myself in the middle of writing this blog post - did any of us made the same mistake I did? Destroyed its customer’s data by running a slightly wrong update in the SQL Server Management Studio?

I knew that there are for sure plenty of us who did that. To find my brothers in arms I asked The Duck to Go for “SQL Server Management Studio rollback”.

I can’t say that I was happy finding out that I wasn’t the only human out there doing mistakes.

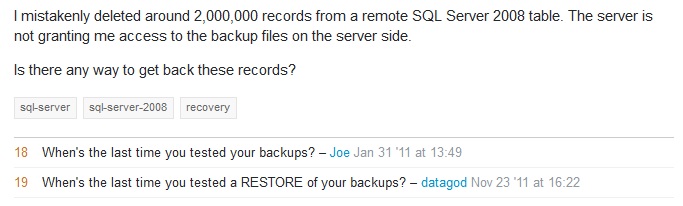

On of us humans mistakenly deleted two million rows from a table.

One can argue that in the era of Big Data and Web Scale and Petabytes million isn’t exactly a big number. But I’m sure my brother in arms was “a little freaked out”, at least as much as I was and I appreciate the general advice given to him in the answer to his question.

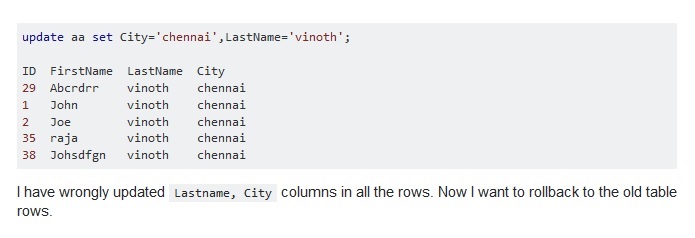

And another one of us gave everyone the same last name and at the same time moved everyone to the same city.

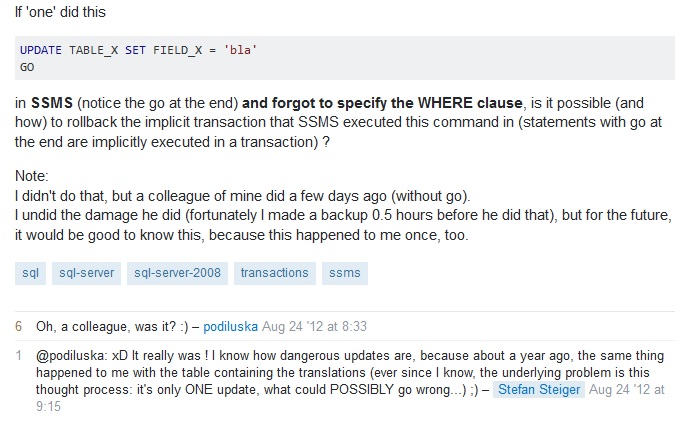

Apparently, forgetting the WHERE clause in updates is something ‘one’ (of us) could always do.

“Oh, a colleague, was it? :)” :-)

I appreciate Stefan’s honest comment that the same happened to him as well. And the remark that “the underlying problem is this thought process: it’s only ONE update, what could POSSIBLY go wrong…”. It just proves the point.

We are only humans after all.

If you made it this far, chances are you might like my next blog post as well :-) Should I let you know when it's out?